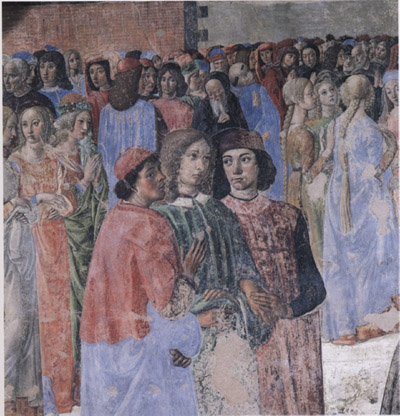

Part of a fresco from the church of San Ambrogio in Firenze, depicting Pico as he's being flanked by his jolly good friends Angelo Poliziano and Marsilio Ficino. I gotta tell ya, it's getting harder and harder to find decent pictures of the guy....

Though Pico’s ontology of the human species is not always consistent, it does follow a certain kind of inner logic. For example, in his earliest written work, a commentary on his friend Girolamo Benivieni’s poem Canzone d’Amore[1], Pico distinguishes between four specific parts that make up the human soul: the vegetative, the sensitive, the rational, and the intellectual. The Oration, written shortly afterward in this period of exceptional productivity that Pico would never again match, confirms this fourfold division, while stressing that it is the unity of man which participates in the nature and essence of all creation that allows him to be “made one with God.”

In the Heptaplus Pico lays out a more elaborate scheme of human nature, consisting of (1) the mortal body; (2) the rational soul; (3) an intervening spirit which serves to connect the soul and the body; (4) the intermediate sensual part we share with the brutes; and (5) the intelligence we share with the angels. Elsewhere in the Heptaplus Pico describes man as being made up of “a body compounded from the elements, and a heavenly spirit, and the vegetative soul of plants, and the sense of brutes, and reason, and the angelic mind, and the likeness of God.” What Pico thus identifies as essential in a human being are the characteristics we share with beings higher than ourselves (angels) and creatures on a lower step of the ladder (plants, animals), those characteristics being the intellect in the case of angels, and the vegetative soul and senses in the case of lower beings. Sometimes Pico mentions these last two together and sometimes not, being content to simply point out that we have something in common with higher as well as lower nature.

Furthermore, there is the unity of God that we emulate, and through which we are able to ultimately achieve the desired deification. Specifically, it is through Jesus Christ that the invisible God is united with His creation. The spirit that Pico talks about seems to be the spirit of life (Pico also equates it with “light”), since without it the heavens could not impart the benefits of life and motion on us. What peculiar to the human being is the rational soul, and it is through this faculty that henosis (A Neoplatonic term connoting union with the One or the ultimate Source) is achieved.

Pico departs from the accepted Aristotelian and scholastic notions which hold that reason is the highest faculty of the soul and follows the Platonists in positing an intellectual or angelic part above the rational. Through this distinction Pico is able to adhere to the Averroistic’ notion of the unicity of the intellect.[2] The Arabic philosopher Averroes (Ibn Rushd, 1126-1198) became quite notorious in the Renaissance with his theory that there is only one shared intellect for all human beings, which caused many disputes among philosophers regarding the perceived merit of this theorem. Philosophically, it was quite attractive, for it could explain the universality of intellectual knowledge, but theologically it was untenable, because it seemed to imply that there was no personal immortality after the death of the material body. Such a matter was central to Renaissance philosophy, because it touched on major questions like the eternity of truth and the capacity of the human mind to grasp this, and the way to account for human behaviour and morality.

The immortality of the soul, the defining mark of humanity, was essential to the salvation of mankind and demonstrates the inescapable link between philosophy and theology, the former often working to strengthen the latter. By positing the rational soul as the fundamental feature of human nature, Pico handily circumvents this problem. The rational soul, the medium trough which we reach to God, is personal and immortal, while the intellect provides reason with the impulse to reach above itself and strive to unity with God. What Pico thus seems to postulate is that the divine intellect illumines our soul, which eventually endeavours to go even beyond this and reach its ultimate source, God.

But as stated before, owing to the pull of sensual appetites the rational soul will not climb upwards to the highest chambers of heaven by its own accord, but needs to be expressly cultivated and Pico proposes a rigorous program for this. After all, “nothing can rise above itself by relying on its own strength” (Heptaplus), and the person attempting to do so has to be sagacious and morally worthy. The count of Mirandola therefore draws up a four part program, echoing the doctrines of the psychological, moral, mystical and ritual aims of philosophy expounded by Neoplatonists and early Church Fathers such as Clement of Alexandria. Simply put, we have to “compete with the angels in dignity and glory” and emulate the ways of highest three orders of angels, namely the Thrones, Cherubim and Seraphim. So we have to be of worthy opinion like the throne, who “stands in steadfastness of judgment”; of contemplative insight as the cherub, who “shines with the radiance of intelligence”; and finally, of proper dedication and love for God like the seraph, who “burns with the fire of charity” (all quotes from the Oration, as if you hadn’t guessed). Pico then moves to illustrate his curriculum by example of Saint Paul and Jacob, and fortifies it by showing its continuity with many other traditions of wisdom, such as that of the Pythagoreans, Plato and the Chaldeans.

Wow. We’re heading into truly glorious abodes now. Better wear some sunglasses or something like that next time so as not to be blinded by the sheer and utter brilliance erupting from you screen! Hoho.

[1] Pico composed this work between 10 May 1486 and 10 September 1486, after he had tried to kidnap a certain Margherita, a wealthy widow who had just remarried a minor de’Medici, but a Medici nonetheless, in Arezzo. Accounts on Margherita’s supposed willingness vary (Pico’s sister swore the lady followed her brother voluntarily), but in any case the young count was caught right before reaching Siena and was lucky to escape with his life. Pico’s retinue was not so lucky however, as some eye-witnesses held that eighteen of his men bit the dust following the reckless episode. All the same, Lorenzo de’Medici was quick to forgive this crime and Pico returned with a pious zeal to his studies.

[2] Pico states this adherence in theses 2>73 & 3>67-69. Actually belonging to the 400 statements that he presented as “not his own”, Pico amplifies Averroes’ claims in such a way as to make them his personal interpretation and it seems likely that he intended to demonstrate the concord of Averroes with Aristotelianism and Christianity.

No comments:

Post a Comment